Phonology

This lesson may seem tediously technical at first, but it is essential. The material presented here may not sink in right away, so come back to it every now and again for review.

In what follows we use a simplified phonetic notation to represent phonemes— namely, a Latin letter between forward slashes, as in /a/. At opportune times, we stop to ask you to identify what Greek letters represent what phonemes. Thus, this lesson is also a review of the Greek alphabet.

There are two categories of phonemes, or distinct units of sound: vowels (/a/, /e/, /i/, and so forth), which form the nucleus of a syllable, and consonants (/b/, /f/, /m/, and so forth), which add audible flavor to that syllable. We begin with vowels.

Vowels

Vowels have two characteristics: quality and quantity. Quality refers to the distinctive sound each vowel makes. When you say, “a-e-i-o-u” (/ey-ī-ay-ōw-yū/), you produce five qualitatively distinct sounds. Quantity refers to the time it takes to pronounce a vowel.

Quantity. In Greek, vowels are either short or long. Α long vowel takes twice as long to pronounce as a short vowel. We identify long vowels by placing a macron (or, colloquially, a long mark) over it, as in /ā/. If there is no macron over the vowel, it is short, as in /a/.

English no longer distinguishes vowels by their quantity, so we cannot hear a quantitative distinction between, say, /a/ and /ā/. However, Ancient Greek speakers were acutely aware of the quantity of their vowels. Therefore, we must know when vowels are long or short, even if we cannot hear the difference in quantity.

Quality. Although English does not have a distinction in vowel quantity, we can hear the difference in vowel quality.

Short vowels in Greek are pronounced /a/ as in “father,” /e/ as in “bet,” /i/ as in “hit,” /o/ as in “top,” and /u/ as in “mutt.”

Long vowels in Greek are pronounced /ā/ as in “father,” /ē/ as in “game,” /ī/ as in “feet,” /ō/ as in “goat,” and /ū/ as in “fool.”

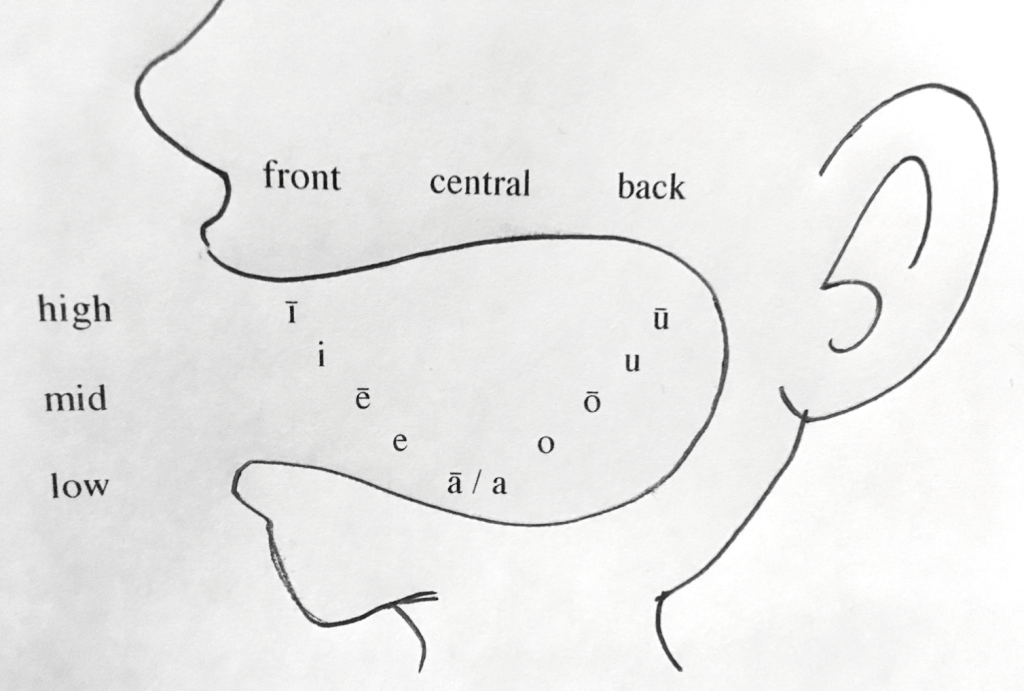

These sounds may be organized visually according to where the tongue is in the mouth when pronouncing them (front, center, or back; high, middle, or low) as follows:

If you pronounce “yaow!,” you pronounce all of these vowels in their proper sequence. Pronounce “yaow!” slowly, and you will feel your tongue move from front high to mid low to back high. In so doing, you may feel—if not even hear—the distinction between the sounds /a/ and /o/, which otherwise are nearly indistinguishable to an English speaker’s ear.

(Q) What Greek letters are used to represent the phonemes in the image above?

Technical Notes:

- The historical pronunciation of eta, η, is complicated. It is regularly pronounced /ē/ by modern English speakers of Ancient Greek, but it may also be pronounced /æ/, as in “hat” and “cat.”

- /a/ and /ā/ are qualitatively indistinct, meaning that they do not differ in the sound they make. However, they are quantitatively distinct, meaning that /ā/ is pronounced twice as long as /a/.

- Originally short υ was pronounced /u/ and long υ /ū/. However, the pronunciation had changed in Ionic and Attic by the Classical Period. The two vowels were fronted: short υ was pronounced /ü/ between /u/ and /i/, like French u and German ü, and long υ was pronounced / ǖ / between /ū/ and /ī/. In Modern Greek, υ now represents a fully fronted /ī/, the conclusion of υ’s long journey forward. That said, because English does not have the sounds /ü/ and /ǖ/, we pronounce short υ /u/ and long υ /ū/.

- A diphthong is a vowel that concludes in the glide /y/, represented by ι, or /w/, represented by υ. The addition of a glide to a vowel does not change the quality of that vowel. Thus, αι is pronounced /ay/, ευ /ew/, οι /oy/, and so forth.

Vocalic nu, Ṇ, is pronounced in the nose as in English “button” /bu’ṇ/. In Greek, Ṇ becomes α after a consonant and ν after a vowel.

The Greek vocalic Ṇ developed from an original PIE vocalic Ṃ. Latin inherited vocalic Ṃ as seen in the accusative singular, for instance rēgīnam, virum, and rēgem. Whereas in Greek vocalic Ṇ becomes either α or ν, in Latin vocalic Ṃ nasalized the preceding vowel: rēgīnam was pronounced /rēgīnã/, virum /virũ/, and rēgem /rēgẽ/. Thus, Latin words written with word-final –m actually end in nasalized vowels. This is why –m appears to elide in poetry.

Here’s a video lesson on vowels:

Consonants

Consonants have two characteristics: place of articulation and manner of articulation.

Place of articulation refers to where or with what in the mouth a consonant is produced. From the front of the mouth to the back of the mouth, consonants are identified as labials (pronounced with the lips), dentals (pronounced with the tongue touching the back of the teeth), velars (pronounced with the back of the tongue raised toward the roof of the mouth), and glottals (pronounced in the throat). For instance, /p/ is a labial consonant, /t/ is a dental consonant, /k/ is a velar consonant, and /h/ is a glottal consonant. Helpfully, every consonant in the word “dental” is a dental.

In English, /d/, /t/, and /n/ are not true dentals. Correctly they are “alveolars,” a term that refers to the sockets of the upper teeth and a place of articulation between dental and velar. However, in Greek they are true dentals.

Here are some consonants. To the best of your ability, and before reading further, organize them according to place of articulation in the chart below.

/b/ /k/ /d/ /f/ /g/ /h/ /l/ /m/ /n/ /p/ /t/ /v/

| Labial | Dental | Velar | Glottal |

Manner of articulation refers to the degree that breath is or is not restricted when passing through the mouth. A fricative is a consonant pronounced with a continuous yet restricted flow of air, as in /f/, /v/, and /h/. In contrast, a liquid is a consonant pronounced with a continuous but relatively unrestricted flow of air, as in /l/. A nasal consonant is similar to a liquid, but it requires use of the nose, as in /m/ and /n/. You cannot pronounce these sounds if you close your nose. Finally, a stop consonant stops the flow of air, as in /p/, /t/, and /k/.

Consonants are sub-categorized as either voiced or voiceless. When pronouncing a voiced consonant, the vocal cords vibrate. When pronouncing voiceless consonants, the vocal cords do not vibrate. In order to feel the distinction between voiced and voiceless sounds, it is best to begin with fricatives.

Hold your throat and pronounce the sound /f/. You should feel no vibration of your vocal cords. Now, if you voice the sound /f/ so that you do feel vibration, you should be pronouncing the sound /v/. Try the same thing with /s/ and /z/. Which one is voiced and which one is voiceless?

The sounds /f/ and /v/ are labial fricatives. The sounds /s/ and /z/ are dental fricatives. In other words, they are pairs within the same categories of place and manner of articulation. They differ only in vocalization.

We may organize fricatives as follows (empty boxes do not mean the sound does not exist in language; rather they are phonemes irrelevant to this discussion):

Here’s a video lesson on consonants: