The Imperative and Other Commands

1st Person Commands

We command ourselves in the 1st person (singular or plural) with the subjunctive. This use of the subjunctive is called hortatory (from Latin hortari, “to encourage”):

| ἀναλάβωμεν οὖν ἐξ ἀρχῆς. | So let’s take up (the topic) from the beginning. |

2nd Person Commands

We command people with whom we are speaking by using the imperative mood. Since usually we are commanding someone to perform an action (aorist) rather than to be performing an action (progressive), normally we use the aorist imperative:

| καί μοι δεῦρο, ὦ Μέλητε, εἰπέ. | And tell me again, Meletus |

Second person commands are often accompanied by a vocative, as we see in the example above.

If we wish to command someone not to do something, we can use μή with the subjunctive. This use of the subjunctive is called a negative command:

| καί μοι, ὦ ἄνδρες Ἀθηναῖοι, μὴ θορυβήσητε! | Hey Athenian men, don’t get upset at me! |

We don’t have to, though. Elsewhere in Plato’s Apology Socrates also says in the imperative μὴ θορυβεῖτε (21a5 and 30c2).

When we command someone to do two things in English, we use two imperatives:

Live long and prosper!

Greek, however, uses a participle and imperative. If there is a clear sequence to the things we are ordering someone to do (that is, to do one thing and then another thing), the aorist participle is used to capture the first command:

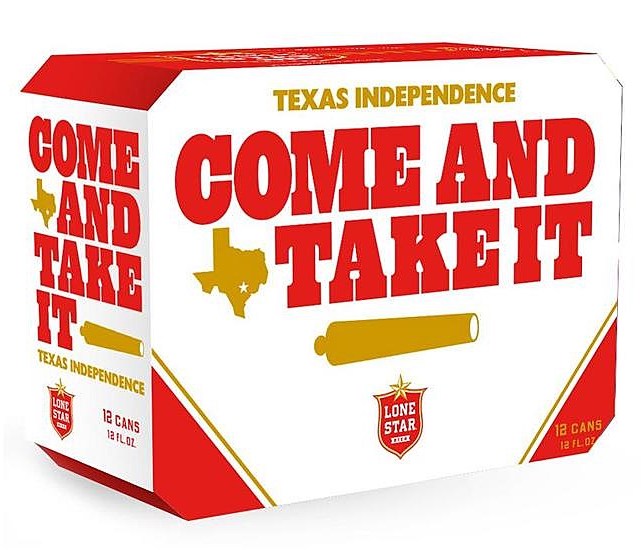

| μολὼν λαβέ | Come and take it! |

—Plutarch, Sayings of Spartans 51.11

Hyperliterally, μολὼν λαβέ is translated “having come, take!” But we shouldn’t translate it this way. Again, where Greek uses the participle imperative construction, English uses the double imperative.

As an aside, supposedly Leonidas, a king of Sparta, said “come and take it” (or better: “come and take them”) in response to the request of Xerxes, the king of Persia, when he asked the Spartans to surrender their weapons. After a few days of battle, that is precisely what Xerxes did. The phrase “come and take it” has been a motto of armed resistance throughout the history of the United States, but it is not clear that it is always used with the original historical context in mind: Leonidas and his Spartan soldiers died in battle and lost their weapons.

Another way to command someone is by using ὅπως with the future indicative, literally “that you will [verb]!” In Greek, an introductory main verb, like “be sure” or “see to it” has been suppressed. So let’s added again in our translation:

| ὅπως τοίνυν ταῦτα μηδεὶς ἀνθρώπων πεύσεται! | So be sure that no one finds out about these things! |

Although πεύσεται (πυθ/σ/εται) is future, we translate it as present because English does not use the future comfortably in this construction.

3rd Person Commands

To command people to whom we are not directly speaking, we use the imperative:

| νῦν παρασχέσθω—ἐγὼ παραχωρῶ—καὶ λεγέτω. | Let him produce (it) now—I yield the floor—and let him speak! |

Other Ways to Express Obligation

To express obligation we may instead use an impersonal verb like δεῖ or χρή. Both take a subject accusative and infinitive construction. It is best to personalize these verbs in our translation after we see how the Greek construction works grammatically:

| με δεῖ ζῆν ἐν δεσμωτηρίῳ. | It is necessary for me to live in prison. (acceptable translation) I should live in prison. (preferred translation) |

Alternatively, we may make a verbal adjective that expresses obligation by adding the marker /τέο/:

| ὅμως τοῦτο μὲν ἴτω ὅπῃ τῷ θεῷ φίλον, τῷ δὲ νόμῳ πειστέον καὶ ἀπολογητέον. | Nevertheless, let it go how the god likes it, and let us obey the law and make a defense. |

Correctly πειστέον (πιθ/τέο/ν) and ἀπολογητέον (ἀπο/λογε/τέο/ν) are passive, but a literal translation is awkward in English: “there must be an obeying of the law” and “there must be a defense.” So as with δεῖ and χρή, it is best to personalize the construction in our English translation.