Uses of the Definite Article

Introduction

Definite Article

The definite article is called “definite” because it defines, or specifies, a noun. For instance, ὁ ἄνθρωπος, “the person,” is a specific person, whereas ἄνθρωπος, “a person,” is an unspecified person. “A” or “an” is called the indefinite article.

In English the definite article is “the.” Greek uses the definite article in many of the same situations that English does:

| ἡ ἄνθρωπος | the person |

| ὁ σοφὸς ἀνήρ | the wise man |

Indefinite Article

There is no stated indefinite article (“a, an”) in Greek. When a noun is not modified by a definite article, it may be translated with an indefinite article in English:

| ἄνθρωπος | a person |

| σοφὸς ἀνήρ | a wise man |

Zero Article

The absence of a definite article in Greek may instead be translated without any article in English. This is called a zero article:

| Λεωνίδας βασιλεύς ἐστι | Leonidas is a king or: Leonidas is king |

Context determines which translation is correct. Normally this poses no problem for interpretation, but see the end of this page for an instance where it does.

Intermediate

<check EGG for full list>

The article is a pronoun, and like other pronouns it can be used substantively (that is, as a noun). Unlike other pronouns, however, this use is limited to a few situations:

The article can modify an adverb, as in οἱ νῦν, “those (living) now,” οἱ πάλαι, “those (living) in the past,” οἱ ἐκεῖ, “those over there,” and so on.

ὀ μέν … ὁ δέ …

can also just be ὁ δέ, right? “but he”

When the pronouns τούτο/ and ἐκείνο/ act as adjectives by modifying a noun, the article is used before the noun. In this case the article isn’t translated:

| οὗτος ὁ ποιητής | this poet |

| ἐκεῖνος ὁ ποιητής | that poet |

how about “all the people” and “the whole city”

attributive and predicate use

Sandwiches

τὸ τοῦ θεοῦ σημεῖον 40b1

καὶ μετοίκησις τῇ ψυχῇ τοῦ τόπου τοῦ ἐνθένδε εἰς ἄλλον τόπον (40c8-9)

the (son of) name

When the infinitive is clearly used as a noun, it is governed by an article. This is called the articular infinitive:

<example>

As an adjective, αὐτό/ means “same” when between the article and noun (attributive position) but “herself, himself, itself, or theirselves” when outside the article-noun pair (<what position?>):

| ὁ αὐτὸς ἄνθρωπος | the same person |

| ὁ ἄνθρωπος αὐτός | the person himself |

| αὐτὸς ὁ ἄνθρωπος | the person himself |

Helpfully, English places the article in the same place as the Greek (before αὐτό/ when it means “same” and before the noun when it means “-self”).

Sometimes the article is used with a proper name. According to Gildersleeve (Syntax 2.537), Greek does this to express familiarity in colloquial language, as a deictic (as in “this Socrates here”), or to distinguish one thing from a group of the same.

Greek uses explicit possessive pronouns (“my, your, her”) when context isn’t obvious or for emphasis. Often the article implies possession, as in καλέει τὸν ἀδελφεόν, “he calls his brother” (Herodotus 2.121B, adapted).

When Greeks refer to the King of Persia, they use βασιλεύς without an article, as if it were a proper name.

Crasis of the article often occurs. For instance, τἄλλα (τὰ ἄλλα), τοὔνομα (Ionic τὸ οὔνομα), ὥνθρωπος (ὁ ἄνθρωπος), and so on.

add ὅδε

Advanced

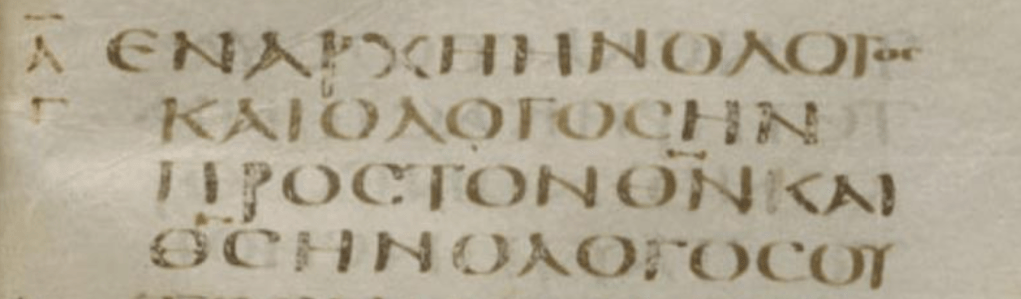

The absence of a definite article can create real problems for the interpretation of a statement. Take the famous opening of the Gospel of John from the New Testament:

| ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος. |

This verse is normally translated:

| In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. |

Of course, “word” is the one word that λόγος almost never means. Greek has other words for “word,” like ὄνομα. But that’s a separate story. It is the last sentence of the verse, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος, that interests us.

The standard translation is, as above, “and the Word was God.” In this instance, the Word (Jesus) and God are equivalent, and the claim that Christianity is monotheistic is not challenged.

However, the sentence may also be translated, “and the Word was a god.” In this case, there is God, a god, and there is Word (Jesus), another god. That is, there are (at least) two gods, and this is a problem for monotheism.

Arguments about the interpretation of θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος go back to Christian antiquity and in part led to the development of a document now known as the Nicene Creed. The Nicene Creed, in turn, condemns those who believe that θεός and λόγος are not the same. This is because most branches of Christianity can’t have θεός and λόγος as distinct things. The grammar of the sentence, however, leaves the issue open.