The Greek Alphabet

The Classical Greek Alphabet Typed

Here is the Greek alphabet as it appears in modern printed texts. It is the same alphabet we use for English—the same these words are written with. Of course, nearly three millennia of stylizing letterforms as the alphabet passed from Phoenicians to Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans — and from there through the Medieval Period and the Renaissance — may make some letters harder to recognize than others, especially in lowercase. A few letters in particular will take some getting used to, for instance ν for /n/, ρ for /r/, χ for /kh/, and ω for /ō/. (Letters between forward slashes represent phonetic pronunciation.)

| lower- case | upper- case | name | pronunciation |

| α | Α | alpha | short /a/ or long /ā/ like “father” |

| β | Β | beta | /b/ like “butter” |

| γ | Γ | gamma | always hard /g/ like “dog“ |

| δ | Δ | delta | /d/ like “dog” |

| ε | Ε | epsilon | short /e/ like “egg” |

| ζ | Ζ | zeta | /zd/ like “Mazda” |

| η | Η | eta | long /ē/ like “lame” |

| θ | Θ | theta | correctly /th/ “tick” but usually /θ/ like “theater” |

| ι | Ι | iota | short /i/ like “hit” or long /ī/ like “heat” |

| κ | Κ | kappa | always hard /k/ like “rock“ |

| λ | Λ | lambda | /l/ like “lullaby” |

| μ | Μ | mu | /m/ like “mouse” |

| ν | Ν | nu | /n/ like “nose” |

| ξ | Ξ | xi | /ks/ like “fox“ |

| ο | Ο | omicron | short /o/ like “hot” |

| π | Π | pi | /p/ like “top“ |

| ρ | Ρ | rho | trilled /r/ like “Madrid” |

| σ/ς, or ϲ | Σ or Ϲ | sigma | /s/ like “sarcastic” |

| τ | Τ | tau | /t/ like “pot“ |

| υ | Υ | upsilon | short /u/ like “mutt” or long /ū/ like “fool” |

| φ | Φ | phi | correctly /ph/ “pot” but usually /f/ like “fantastic” |

| χ | Χ | chi | /kh/ like “cop” |

| ψ | Ψ | psi | /ps/ like “popsicle” |

| ω | Ω | omega | long /ō/ like “oats” |

Be sure to memorize the Greek alphabet in this order. Otherwise you will have trouble looking up words in the dictionary.

For typing Greek on a Mac, see here. For typing Greek on a PC, see here.

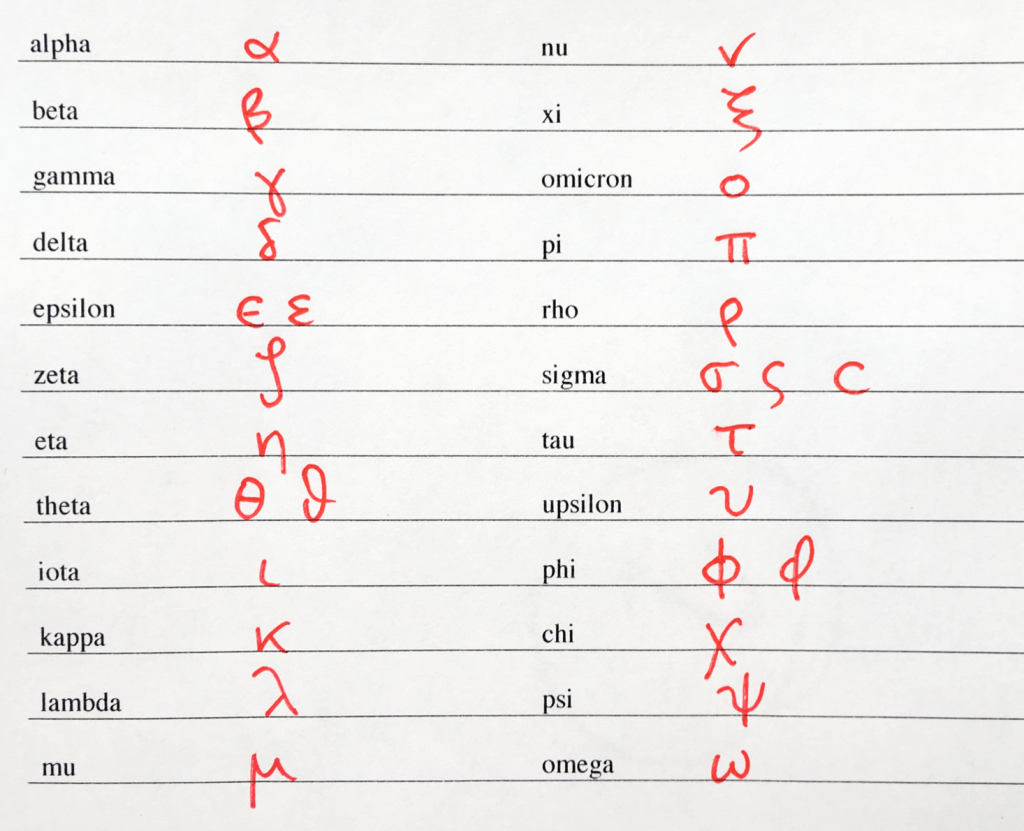

Classical Greek Alphabet Written

Here are the same letters written by hand:

See this video for how to write the Greek alphabet by hand:

Letterforms of Sigma (σ, ς, and ς)

Sigma has several forms. σ is used at the beginning or in the middle of a word, and ς is used at the end, as in ποσις, “beverage, drink,” or συς, “swine.” Alternatively, one may use lunate sigma, ς, throughout, as in ποςις and ςυς. Modern convention prefers the use of σ/ς, but ς is also acceptable. There is no difference in pronunciation: σ, ς, and ς are all pronounced /s/.

Letter Combinations

The digraph ου is pronounced /ū/ as in “food.” The term digraph refers to two letters used to represent one phoneme, or single unit of sound, as in English “oo” /ū/ and “ph” /f/.

In the combinations γκ, γγ, γμ, γχ, and γξ, the first γ is pronounced /ŋ/ as in “going” or “English.” This sound is called angma. This pronunciation should be natural when you pronounce the following words:

| αγμα | πραγμα | συγκινδυνευει |

| λαγχανω | αγγελος | ελεγχος |

In theory, any vowel can conclude in what is called a glide, either /y/, written ι, or /w/, written υ. A vowel followed by a glide is called a diphthong. Here is a list of all diphthongs in Greek. English does not have as many comparable diphthongs, so some examples are only approximate.

| αι /ay/ | as in “hi“ | αυ /aw/ | as in “ouch” |

| ει /ey/ | as in “hey“ | ευ /ew/ | as in “new” but with e pronounced* |

| ηι or ῃ** /ēy/ | also as in “hey“ | ηυ /ēw/ | also as in “new” but with e pronounced |

| οι /oy/ | as in “boy“ | ||

| ωι or ῳ** /ōy/ | also as in “boy“ | ωυ /ōw/ | as in “grow“ |

| υι /uy/ | as in “buoy“ |

* ευ /ew/ may be uncomfortable to pronounce in English, since English doesn’t have this diphthong. Sometimes people pronounce ε and υ separately, making vowels of both and thus two syllables. This, however, is incorrect.

•• In long vowel diphthongs with ι, the ι is usually written underneath the vowel. See iota subscript immediately below for more.

In these letter combinations, if one is supposed to pronounce the glides ι or υ separately as a vowel, and therefore as a separate syllable, a diaeresis ( ̈ ), will appear on it. This means that the two vowels in what otherwise looks like a diphthong are to be pronounced separately, as in παρηϊδα (/pa-rē-i-da/), “cheek.”

Iota Adscript and Subscript

By the end of the 2nd century BCE, the glide ι following the long vowels ᾱ, η, and ω was no longer pronounced and also ceased to be written. Of course, ι is helpful for interpreting morphology. Manuscripts written without the ι were corrected to include it, but due to lack of space in the text it was written underneath the vowel it accompanied:

αι > ᾳ*

ηι > ῃ

ωι > ῳ

* This happens when the α is long. If the α is short, the diphthong remains αι.

This ι is called iota subscript, and most modern editions of ancient texts use it. Ancient inscriptions and papyri keep ι in line with the text (this is called iota adscript), and some modern editions do too.

The Phoneme /h/ and Breathing Marks

Greek words spelled with word-initial ρ, rho, in fact begin with /h/, an initial breath of air that sounds like the h in “hat.” This is why Greek words borrowed into English are spelled rh-, as in “rho,” “rhythm,” and “rhyme,” though correctly they should be pronounced /hrō/, /hriθṃ/, and /hraym/, respectively. To indicate that the Greek word begins with /h/, a rough breathing mark ( ̔), which represents the sound /h/, is placed over the ρ, as in ῥω, ῥυθμος, and ῥυμη. The technical term for this initial breath of air is spiritus asper, or “rough breath.”

Greek words that begin with vowels may also have this initial /h/ breathing. When they do, a rough breathing mark is placed over the word-initial vowel (or glide in a word- initial diphthong):

| ἁλς | /hals/ | salt; sea |

| εὑρηκα | /hewrēka/ | I’ve found it! |

If, however, the word begins with a vowel but does not have an initial /h/ breathing, a smooth breathing mark ( ̓), is written over the word-initial vowel (or glide in a word- initial diphthong):

| ἀγγελος | /aŋgelos/ | messenger |

| εὐ | /ew/ | well |

Consider these breathing marks distinct letters. Every word-initial vowel has one. Without a breathing mark, the word is spelled incorrectly. Writing αγγελος instead of ἀγγελος is effectively the same as writing “onest” and “our” instead of “honest” and “hour.”

Additional Letters and Sounds:

Digamma, Yod, Vocalic Nu, and Laryngeals

ϝ is an archaic Greek letter called digamma (the modern name) or wau (the ancient name). It represented the sound /w/, as in “wow!” The letter fell out of use by the Classical Period, and the sound /w/ was instead represented by υ. As a result, υ may be either a vowel (/u/ or /ū/) or a consonant (/w/).

Reading Morphologically uses ϝ when it helps clarify how words are formed. Knowing where digamma was also helps identify cognates between Greek and English, as in ϝοινον “wine,” ϝεργον “work” and σϝηδυς “sweet.”

The letter J is called yod. It represents the phoneme /y/, as in “you.” It is not a letter in the Greek alphabet. In printed texts, it is represented by consonantal ι. This book uses J when it helps clarify how words are formed.

The letter Ṇ represents a sound called vocalic nu, pronounced in the nose as in “button,” /bu’ṇ/. Like J, it is not a letter in the Greek alphabet, but this book uses it when it helps clarify how words are formed.

Lastly, the non-Greek letters H1, H2, and H3 represent reconstructed phonemes in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) called laryngeals. It is uncertain exactly how these laryngeals were pronounced, but they were doubtless consonants produced in the throat. They became the vowels ε, α, and ο, respectively, and explain instances in which vowels behave like consonants.

Punctuation

Greek has periods (.) and commas (,). The Greek semicolon is a raised dot (·), and the Greek question mark looks like an English semicolon (;).