Indo-European Comparative Linguistics

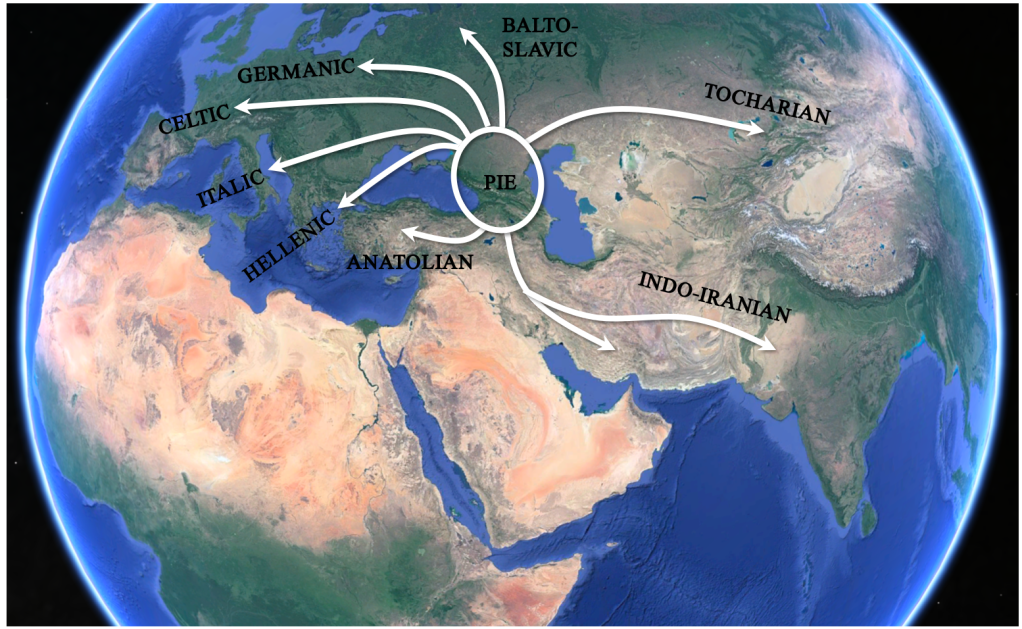

The story of Ancient Greek begins with a people called the Indo-Europeans. They lived on the Pontic-Caspian steppe somewhere between, say, 5000 and 3000 BCE. During that time, groups of Indo-Europeans migrated west into Europe, and south and east into Asia. They took with them their language, which today we call Proto-Indo-European (hereafter PIE), and their culture, which included, among other things, patriarchy, belief in a king sky god named Dyēws Ph2tḗr (“Father Light”), heroic poetry, and a love of horses.

Language inevitably changes. The PIE spoken by these migratory groups evolved into new Indo-European language families: Tocharian, Indo-Iranian, and Anatolian in Asia; and Balto-Slavic, Celtic, Germanic, Italic, Albanian, and Hellenic in Europe. Daughter languages were born, including Vedic Sanskrit and Old Persian in the Indo-Iranian language family, Hittite in the Anatolian language family, Latin in the Italic language family, and Ancient Greek in the Hellenic language family. Many modern languages descend indirectly from PIE, including English and German in the Germanic Language family, Russian in the Balto-Slavic language family, Hindi from Sanskrit, Farsi from Old Persian, and the Romance Languages (Italian, Spanish, French, Romansch, Romanian, and many others) from Latin.

Because Indo-European languages have a common ancestor, shared linguistic (and sometimes cultural) features are observable between them, despite the immense geographical range, from western Europe to India, where Indo-European languages are spoken. For instance, the original Indo-European sky god, Dyēws Ph2tḗr (“Father Light”), becomes Dyáuṣ Pitṛ́ in Vedic, Zeus Patēr in Ancient Greek, and Iuppiter (Jupiter, Jove) in Latin. He is also found in Old English as Tíw, as in Tuesday. While the god Dyēws Ph2tḗr evolved differently in these cultures, these subsequent permutations of him share the same linguistic root reflecting an original Indo-European conception of him as a king god of daylight.

There are no surviving material remains of the Indo-Europeans, and there are no written records of their language. However, linguists are able to reconstruct PIE, their language, from shared features in daughter languages. It is tempting also to reconstruct an original Indo-European religion and society from shared features in later Indo-European cultures, but this is fraught with pitfalls due, among other things, to cultural changes that resulted from exchange and intermixing with neighboring cultures. Millennia separate the Indo-Europeans from the first meaningful evidence of subsequent Indo-European civilizations, and there are so many variables involved in cultural development that reconstructing details of an “original” Indo-European culture is all but impossible. It is for this reason that the name “Indo-European” refers simply to speakers of a shared language, not to any sort of homogeneous culture. Culture isn’t really relevant to the topic at hand, anyway.

Indeed, the frabricated notion of an “original” Indo-European culture brings us to the truly dark side of Indo-European studies. In the 19th century, it was erroneously proposed that the Sanksrit word Aryā , “noble,” was the Indo-European endonym (“name a group calls itself”), and that the Germanic people were the original Indo- Europeans, or “Aryans.” The Nazis and other white supremacists subsequently racialized the term “Aryan,” redefining it (and therefore “Indo-European,” for which “Aryan” now stood) to designate white skin and blond hair, not language. They appropriated the swastika (“well being” in Sanskrit), an Indo-European symbol found in art across the Indo-European world, as the symbol of this ideology. They used the belief in a fictitious “master race” to justify horrendous crimes against humanity, including genocide.

The idea that any language or culture (or genealogy or religion or ethnicity) is “pure” is simply nonsensical. Germanic people are no more “pure” or “authentically Indo-European” than Indo-Iranians, from whose language the word “Aryan” was borrowed in the first place. Indeed, ancient Greece — often cherry-picked for claims of European and white cultural supremacy — as well as the three Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), are complex blends of European, Asian, and African cultures. Their richness is due precisely to this diversity. Wearing pants, using soap, kneeling in church, drinking beer, and not speaking Ancient Greek are among the many distinctly “barbaric” (i.e., non-Greek) elements in modern western cultures. To ignore the melting pots responsible for ancient and modern societies is to engage in willful self-deception. Indeed, much of the joy in studying the ancient world is to see how foreign we are to them, and they are to us.

That said, comparative linguistics nonetheless gives us a deeper understanding of Indo-European languages. Take for instance the Druids, the priestly class of ancient Celtic society. Very little direct evidence about them survives, but the etymology of the word Druid sheds light on Celtic religion.

<insert image from Asterix?>

“Druid” is likely a compound of two PIE roots, *deru- and *wid-. (The symbol * before a word means that the word is reconstructed or hypothetical. Remember that we do not have written evidence of PIE, so all PIE words are reconstructed.) *wid- is a verbal root that originally means “see.” It is found, for instance, in the Latin verb videō (/wideō/), “I see.” It develops from “see” to “know,” referencing knowledge one acquires through sight. Thus, Vedic scripture contains “wisdom” (an English word also from *wid-), and “history,” from Greek *widtoria, begins as an investigation into things one observes. Thus, Druids were those who saw and therefore knew “dru-.”

The PIE root *deru-, whence the dru- in Druid, is an adjective that means “hard,” as in Latin dūrus. Its semantic range developed to mean both “tree” and “truth” (both from *deru-). It is no wonder, then, that “hard” facts are true! So perhaps the Druids had knowledge of truth, and perhaps they saw this truth in nature—and specifically in trees.

The Greeks, too, held the oak tree, drus, in particularly high esteem. For instance, the ancient oracle of Zeus (whose name means “Light”) and his original wife, Dione (whose name also means “Light”), at Dodona in northern Greece believed that the rustling of leaves of sacred oak trees was prophetic.

While we must be cautious about making broad claims about Indo-European conceptions of knowledge and trees, comparative linguistics give us the ability to speculate about certain particular cases — who the Druids were, how Greeks once conceived of history, or why they thought the rustling of certain tree leaves was prophetic. Comparative linguistics also helps us find grammatical similarities between Indo-European languages. As a result, while learning Ancient Greek you simultaneously build a foundation for learning other Indo-European languages. If you already know an Indo-European language, like Latin, your knowledge of that language will improve by learning Greek from this website’s linguistics approach.